Not really. But I'm a bit map-obsessed myself, and Jeopardy!-obsessed, so it was a match made in heaven.

I wasn't entirely sure what to expect with Jennings' Maphead. Starting off I thought maybe it would be a collection of "weird geography facts" -- the most remote inhabited island (Tristan da Cunha), the northernmost inhabited settlement (Alert, Nunavut), the capital of Burkina Faso, (Ouagadougou, you will forever be in my heart). But it turned out to be so much more.

Jennings manages to cover every aspect of map geekdom you could imagine -- map collecting, geocaching, savant geography, fictional maps, Google Earth -- you name it. Every chapter includes his own personal experiences, along with some really interesting interviews. He channels Sarah Vowell, albeit with less Rush Limbaugh bashing.

More than anything it's about cartophilia -- pure obsession with everything maps and geography. I'm not certain I could legitimately call myself a maphead, but I do spend upwards of 2-3 hours every week zooming in to every nook and cranny of Google Earth and Maps. And I did have a Middle Earth poster hanging in my dorm (right next to a katana-wielding Uma Thurman). As a fifth-grader I won our elementary school's branch of the National Geographic Bee, to the delight of my 9 year old self. My prize was an inflatable globe and all was right with the world. Later I joined the high school's social studies Academic Competition Conference team (M.A.C.C. shoutout!), then later the Scholastic Bowl to further satisfy my trivia lust. Sure I answered some boring questions about William Henry Harrison, but really I did it so I could memorize river names in China and the heights of North American mountains.

It was neat to read about other people who love maps as much as I do. People who spent more time studying the two-page fold at the front of every world history book than inside its pages. Maps are mesmerizing and universal. Their visual language can be fundamentally understood by nearly everyone on the planet, even for those stubborn individuals who claim they're "bad at maps." And perhaps paper maps are falling by the wayside in the digital age. That doesn't mean the idea of maps themselves is going extinct. If anything, I feel the advent of GPS and digital maps are sparking a renaissance in geographic awareness.

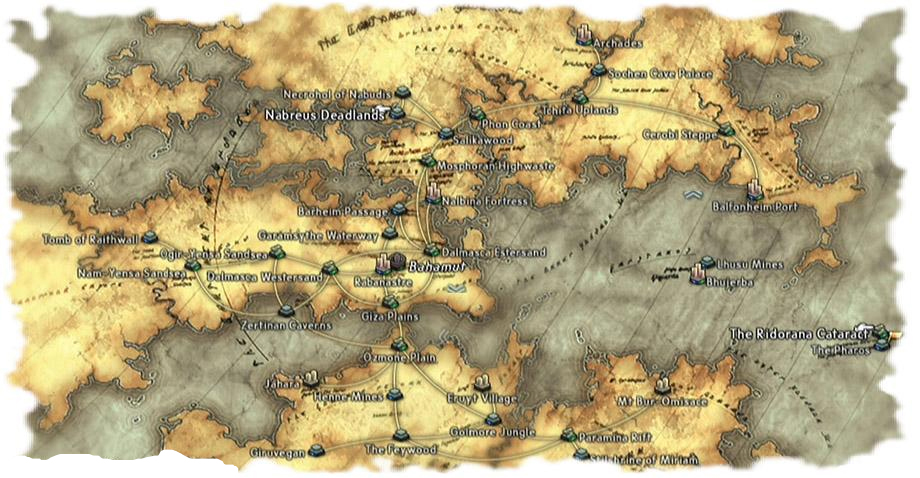

The one area I feel Jennings could have touched on but didn't is the vast use of maps in video gaming. It's a pretty recent medium, but widely popular, and I thought it deserved a few paragraphs in his chapter on fictional maps. Try playing a modern video game without a map. There aren't too many out there. Even the classic Legend of Zelda had a sprawling map that helped you keep clear of the Lost Woods. And some are workshops in map making itself. Try to take 5 steps in the Great Crystal in FFXII without getting lost -- it's nearly impossible. No map is provided, so players have to break out a pen and paper (or google, if you're lazy) if they want to find Ultima. Resident Evil, Doom, Grand Theft Auto, Silent Hill, Dead Rising,...Super Mario Bros 3. Maps, maps, and maps. Or take a game like Borderlands which uses maps in combination with a GPS-esque positioning and compass system. GPS has only been around since 1993, but video games have been representing your person on a map via moving triangle since at least 1992, when Doom was being developed. I'm sure it was used even earlier. And like Al Franken, who can draw a near-perfect map of the U.S. from memory, gamers memorize their landscapes as well, as seen on Mapstalgia, a tumblr dedicated to drawing video game maps from memory.

Oh FFXII's Ivalice, you're the best place ever that doesn't actually exist

Speaking of video games, Maphead introduced me to a new hobby: a video game played in real life called geocaching. Geocaching is the act of hunting hidden caches around the world using a GPS device. You're given the coordinates of a cache's location, or sometimes a puzzle you solve to get these coordinates, and you travel to that location to find a container. Usually the container just holds a log sheet and a few trinkets. There's no material reward for your adventure, just the thrill of the find and a chance to visit somewhere new. Geocaching.com is the most popular site to find and log your geocaching adventures. I put in Roanoke's address and found there are hundreds of them in my area. One location I can actually see from my apartment window. I don't have a GPS enabled device, but given the clues listed on the website I tried to find it the other day. No luck, but I'm still hooked. Looks like I'll be saving up $80 so I can go treasure hunting.

I've blabbered enough. Here are a few passages from the book:

...during FDR's "fireside chats," he often instructed his listeners to follow along with him at home on their world maps, as he described events in both theaters of World War II. Not so with today's far-off wars. Most of us could look at a map, but we probably won't. Instead, we'll just make decisions that are less and less informed--at the ballot box, sure, but in other ways too: investment decisions, consumer decisions, travel decisions. Some of us will take jobs in public policy or be elected to national office, and lives will start to hinge on the decisions we make.

"I can see Russia from my house!" (see also: "Uzbekibeki-bekibeki-stanstan")

...geography seems less relevant than ever in a world where nonstate actors--malleable entities like ethnicities, for example--are as powerful and important as the ones with governments and borders. Where on a map can you point to al-Qaeda? Or Google, or Wal-Mart? Everywhere and nowhere.

He never goes anywhere without shopping for a souvenir tie printed with a local map. Sometimes he comes up dry, though--he just got back from Chile, where there wasn't a single map tie to be found.

"That's weird," I respond. "I thought skinny ties were coming back!" Dead silence greets my attempt at South American geographic humor. I see now that the world's largest array of cartographic neck-wear is nothing to joke about.

Well, I laughed.

The Northwest Passage and the South Pole had fallen by the time The Hobbit was released, and Hillary scaled Everest the same year Tolkien drew the maps for The Fellowship of the Ring. There were, effectively no blank spaces left on the map. Maps of the Arctic tundra of Darkest Africa didn't cut it for young adventurers anymore; they had to look elsewhere for new blank spaces to dream about. And so they found Middle-earth, Prydain, Cimmeria, Earthsea, Shannara.

I wonder aloud to Brandon and Isaac if fantasy readers crave immersion as a form of escape because they're dissatisfied in some way with real life. I guess I've wandered a little too close to suggesting that fantasy nerds are all hopeless misfits, and Brandon calls me on it. "Look, I love my life, and I love fantasy. I have no reason to escape my world, but I still like going someplace new. Do people who like to travel hate where they live? When you open a fantasy book and see a map filled with new places, it makes you want to go explore them."

It's human nature to want to explore. We are curious cats. But we can't all afford to traipse off to east Asia whenever we feel like it. What's the best way to explore when you're stuck in a suburb? Reading a book. Watching a movie. Creating a new landscape from your imagination. It's a way to satisfy that itch to explore, short of donning a safari hat and running off into the jungle. It has nothing to do with satisfaction/dissatisfaction with your real life.

Basically if you've ever read and enjoyed any piece of fiction ever, you have no right to judge fantasy readers or writers. They're just taking it to the next level. And that level includes dragons and trolls, damn it.

And it's not like fantasy maps are a new concept anyway. Here's a 1695 map showing the supposed location of the Garden of Eden. Or this 16th century map showing an awesome collection of sea monsters surrounding Scandinavia for some reason. I'm surprised Beowulf hadn't killed them all.

If you're a lover of fantasy maps, but bored with the plain ol' Euro-centric world map, take a look at this:

Don't tell me that that doesn't blow your mind, even just a little bit. Of course being a Mercator it still makes Russia look like King Kong, but it's a nice way to flip your perspective on the appearance of our world. Or what about this Antarctica-centric map? Things are starting to look a lot like Galbadia.

I do have one bone to pick with the author, and that is his discussion, and attitude, towards women and geography. When discussing the National Geographic Bee in the seventh chapter he notes the under-representation of girl competitors on stage:

My immediate assumption is that the root of the achievement gap is spatial ability. Tests on gender and navigation have found that women tend to navigate via landmarks...which ties in nicely with the evolutionary perspective: early men went out on hunting expeditions in all directions and always needed to be good at finding their way back to the cave, developing their "kinesic memory," while women forage for edibles closer to home, developing "object location memory."

A few paragraphs earlier he explains away the over-representation of Asian American competitors as due to the fact that "Indian American culture so values this kind of educational success." I'm calling bullshit. Claiming that women have poor spatial ability because of evolution, then turning around and saying the only reason there aren't more white boys on stage is because of "an elaborate farm system for Indian bee nerds" is irresponsible. The performance of both demographics have everything to do with societal factors. And Ken's blurb claiming half the human population is biologically inclined to be worse at something isn't helping things.

Now that that's out of the way, I have to say it took me forever to read this book. Not because it was burdensome or boring (quite the opposite!), but because I read all of it with Google open. Every obscure island mentioned, every strange border, every previously unknown term, I had to look up. And as with Wikipedia surfing, before you know it you're looking up flight costs for your hypothetical trip to Tiksi, Russia and two hours have passed.

So if you're like me and want to take a tour of every strange and obscure point on the planet, but can only afford the armchair variety, I'll save you some footwork (fingerwork? that sounds wrong) and post some links to peruse below. Some are mentioned in Maphead, others were found during my web-meandering.

Point Roberts, WA - peninsula tip hanging south from Canada, only considered to be part of the United States because it's below the 49th parallel.

Rockall - an extremely tiny uninhabited rock islet north of Britain.

Hashima Island - an uninhabited island off the coast of Japan once housing a coal mining facility from 1887-1974, now completely abandoned.

Bir Tawil - an 800 square mile terra nullius (no man's land) between Egypt and Sudan, unclaimed by any country.

Vulcan Point - a triple island -- an island on a lake on an island on a lake on an island -- in the Phillipines.

Yakushima Island - home to one of the oldest, untouched primeval forests in the world. Gorgeous.

Santa Cruz de Isolte - the most densely populated island on Earth.

Have fun, cartophiliacs.

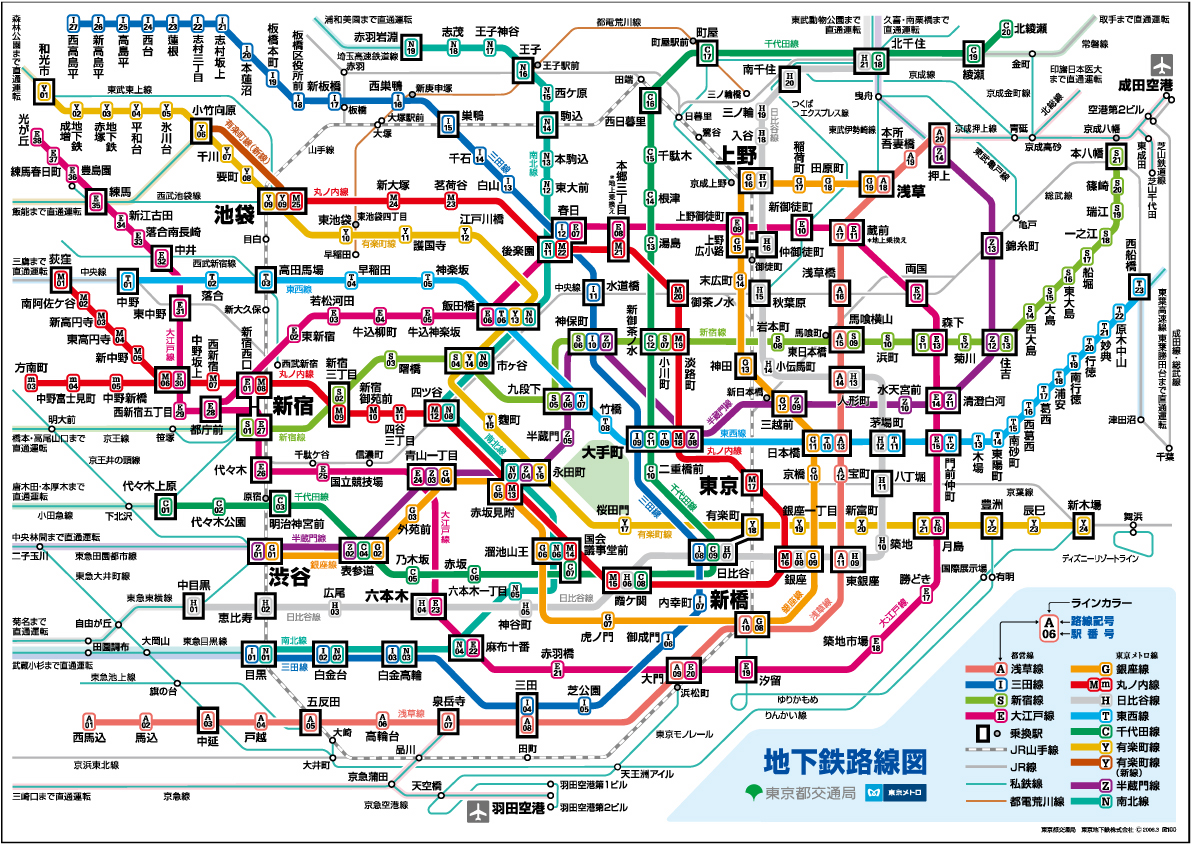

Update: One more thing, in response to Ken's insistence on female map ineptitude -- in 2008 I managed to navigate Tokyo's metro system, having never used subway transportation before, only a rudimentary knowledge of the Japanese language, the inability to read kanji, and every single station map looking like this:

SUCK IT.

No comments:

Post a Comment